In neurology when we use the term weakness we mean a loss of power or loss of Motor strength i.e. a motor deficit. The other way to describe this is focal motor deficit. Patients on the other hand do not come to their doctor stating ‘I have a motor deficit’ or ‘I have a sensory deficit’, rather they use descriptive terms. Clinicians are trained to recognize how patients try to express themselves. During the clinical encounter the first step is usually to determine what the problem is. ‘doctor I feel weak’ does the patient mean they have reduced power, or do they mean they are tired or fatigued, or do they mean something else. When patients say ‘my leg has gone all numb’ are they trying to describe a sensory deficit in the modality of touch, or are they trying to say that they can not move it. Often the patient says that the limb feels “heavy” when describing a focal motor deficit.

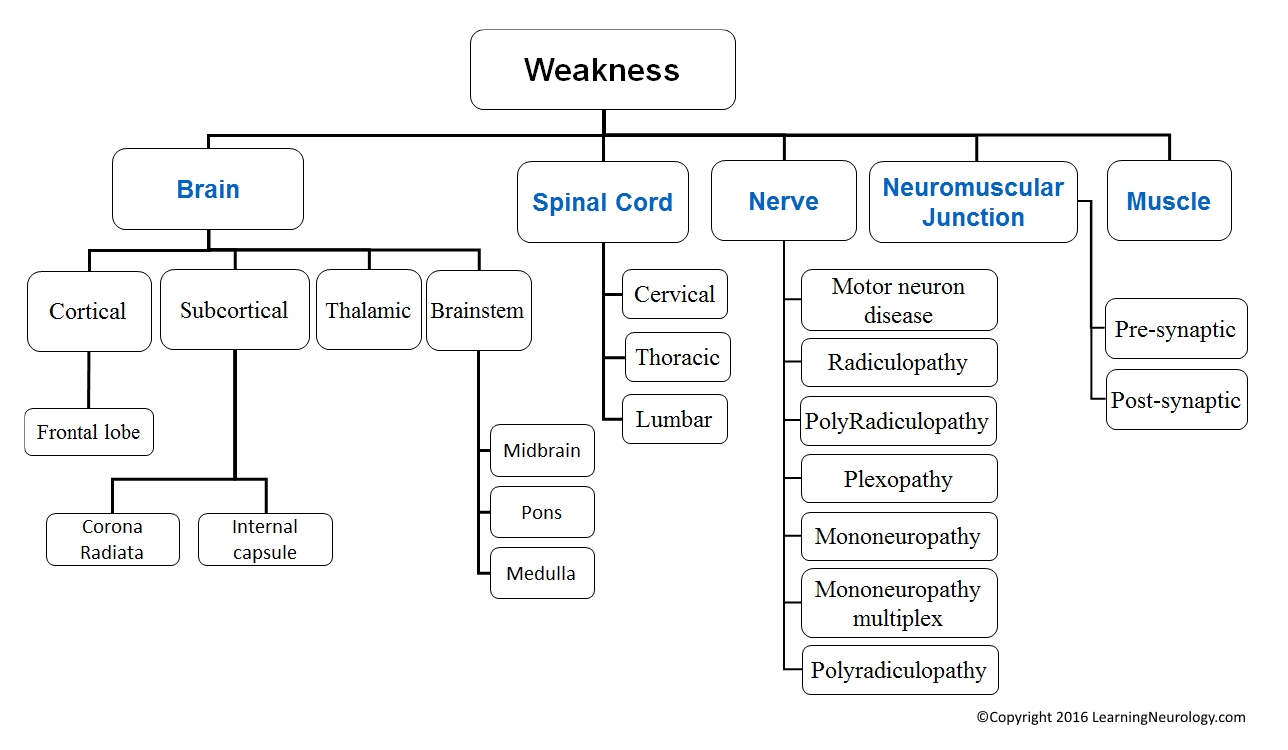

As with most deficits of neurological function, after determining what the problem is, an attempt is made to localize the lesion. Following that, a differential diagnosis is arrived at based on the location of the lesion & all other features of the patients history & examination. Then appropriate investigation & treatment plans can be designed for the patient.

Neurologist summaries this process by the three most important questions that are answered in succession:

- What is the neurological problem/presentation? establish that the presentation represents a focal motor deficit rather than another issue.

- Where is the lesion? determine the localization within the nervous system of the lesion.

- What caused the lesion? determine the etiology of the lesion; i.e. likely vascular, infective or neoplastic etc

- What are we going to do about it? devise an investigation and treatment plan.

This process is not confined to neurology or motor deficits, clinicians use it when dealing with vomiting for example. Is it vomiting or hematemasis, is it GIT or systemic, is it in the foregut (gastric outlet obstruction), midgut (small bowel obstruction), or hind gut (large bowel obstruction). What caused it chronic duodenal ulcer, pyloric stenosis, tumour, adhesion, hernia, meningitis, etc. What are we going to do about it? Ultrasound, CT, ERCP, blood tests, amylase levels, fluids, antibiotics, surgery etc.

However this process is more evident & elegant in neurology & especially with localising a motor deficit.

The distribution of deficits i.e. the pattern of weakness is the primary way to narrow down the possible locations in the nervous system that might explain the deficits. A working knowledge of functional neuroanatomy is necessary for this task. For example hemispheric lesions will cause contralateral weakness, however spinal cord lesions and lower motor neuron lesions will cause ispilateral weakness. High lesions in the spinal cord will likely affect the arms, whereas lesions in the thorax or lumbar spinal cord will spare the arms. There are some notes at the end of this page to help summarize this.

Another important point is to look for neighboring signs and symptoms i.e. signs of dysfunction outside the motor tract that might help tell you where the lesion is. For example when weakness is accompanied by cortical signs, aphasia, agnosia and apraxia, the lesion is likely close to the cortex or juxta-cortical (next to the cortex). If the weakness is accompanied by cranial nerve dysfunction than the lesion is likely in the brain stem. If there are crossed signs i.e. ipsilateral facial palsy and contralateral hemiparesis then the lesion is in likely in the pons on the same side of the facial palsy. Weakness accompanied by bowel, bladder and erectile dysfunction suggests a spinal cord lesion; particularly when there is a sensory level.

As far as etiology goes, the temporal features are often the most useful. If the weakness occurs suddenly that suggests stroke. If it is subacute in onset then demyelinating disease or a tumor may be more likely. If the symptoms resolve on their own and recur then demyelinating disease is more likely than tumor. If the symptoms rapidly improve and recur then a transient ischemic attack or stroke is more likely in the differential diagnosis. However, the etiological approach is tailored to the localization of the lesion. If the weakness was recurrent or fluctuating but you had localized it to the neuromuscular junction, then myasthenia gravis would be the highest on your list.

The last step involves planning the investigations and treatment. This is tailored to the differential diagnosis that you arrived at. We typically assess the most likely disorder, the most treatable and the most important one not to miss.

Another point to make is one of terminology. ‘Weakness’ as used by clinicians implies that there is decreased power, in other words a motor deficit. This power can be graded. This is clinically useful in monitoring the course of some of the patients, in either an inpatient or outpatient setting. For example a patient with a power of 3 in his right lower limb, now has a power of 1. Why did he progress, is it expected, are we going to do anything about it, if so what?

4 basic patterns of features for motor deficit:

Upper motor neuron lesion features:

- Little muscle atrophy

- Spasticity

- Weakness or paralysis

- Increased reflexes, extensor plantar response (Babinski positive), absent superficial abdominal reflexes, with or without clonus

Lower motor neuron lesion features:

- Muscle atrophy, fasciculations

- Flaccidity i.e. hypotonia

- Decreased or absent reflexes (more prominant with demyelinating disease), flexor plantar response (Babinski negative), normal or absent superficial abdominal reflexes

Neuromuscular junction features:

- No atrophy

- Normal or reduced tone

- Weakness: patchy i.e. doesn’t conform to an anatomic structure, fluctuation with time & exercise i.e. fatigability

- Normal or depressed reflexes

- No sensory changes

- Fatigability of weakness or facilitation of power. Weakness that gets worse or better with muscle exertion.

Myopathy features:

- Muscle may be normal, wasted or pseudohypertrophied, depending on the disease & time of presentation

- Weakness, usually more proximal than distal

- Usually proximal rather than distal weakness, but there are distal myopathies. Also, some myopathies are restricted to certain muscle groups e.g. ocular and pharygeal muscles

- Usually symmetric weakness

- Pure motor weakness without sensory signs

- Tendon reflexes are usually preseved until late in the disease. They may be depressed later on in the disease. Normal abdominal & plantar reflexes

- Make an attempt to characterize which muscle groups are affected: upper limb shoulders girdle (deltoids, rotator cuff), lower limb girdle (gluteal, quadreceps), distal muscles (finger flexors, peroneal muscles), occular muscles, pharyngeal muscles, diaphgram or heart.

- Bowel and bladder sphincters are usually spared.

If upper motor neuron lesion:

Cerebral cortex:

- May be associated with dysfunction of higher centers e.g. Broca’s aphasia etc.

- May conform to the territory supplied by one of the cerebral arteries:

- Contralateral Legs: anterior cerebral artery

- Contralateral Face & arm: middle cerebral artery

- Vision: posterior cerebral artery

- Hemiparesis: middle cerebral artery

- If parasagittal, it affects both legs & then maybe both arms

- Subcortical lesions can produce similar symptoms to the cortical ones.

Internal capsule:

- Usually a severe “dense” hemiparesis with or without sensory symptoms, because the fibres are packed closed to one another.

Thalamus:

- Sensory:

- Loss of sensation of one half of the body, pain in one half of the body

- Thalamic pain a.k.a. thalamic syndrome: pain on touching the skin

- Motor: hemiparesis, less common than sensory dysfunction

- Cognitive dysfunction because of reciprocal connections with the cortex:

- Frontal network syndrome may occur; i.e. symptoms/signs of frontal lobe disease

- Aphasia may occur with left-sided lesions.

- Agnosia may occur with right-sided lesions.

- Decreased level of consciousness due to interruption of the reticular activating system

Brainstem:

- Cranial nerve involvement

- The D’s of brainstem lesions:

- Diplopia ‘Double vision’, dysphagia, dysarthria, ‘dizziness’ Vertigo & ataxia

- Crossed deficits may occur: e.g. with a left-sided lesions: a facial palsy on the left side & hemiparesis of the right side

- The D’s of brainstem lesions:

- Bilateral signs may occur e.g. quatraparesis

- Later on or in larger lesions, respiratory function may be impaired

- If above C5: quadraparesis more commonly than hemiparesis that spares the cranial nerves

- If below T1: the arm is completely spared but the legs are affected

- A sensory level is very helpful

- Lesions are usually bilateral:

- Associated with bladder or sexual dysfunction

- If unilateral:

- Ipsilateral motor deficit, vibration & proprioception impairment

- Contralateral loss of pain & temperature

- a.k.a. Brown-Sequard syndrome

- A focal lesion may cause an associated lower motor neuron (LMN) lesion at the level, especially if the process also affects the nerve root, we call this a myeloradiculopathy (this is rare though)

- T1-T9 lesions interrupting the sympathetic outflow, Neurogenic shock may occur: this is a form of distributive shock occurring with bradycardia & loss of vascular tone ‘hypotension’. T1-T4 innervate the heart, T5-T9 innervate the vessels

If lower motor neuron lesion:

Is it with or without sensory deficit? What is the pattern of dysfunction? Does it fit within the distribution of one nerve, within the distribution (segment) of one nerve root, within the distribution of many nerves or glove and stocking.

- Alpha motor neuron:

- Fasciculations

- Atrophy

- Usually develops asymmetrically i.e. starts in one limb & then other limbs are affected, so at a late stage it affects all the limbs

- May develop in the bulbar muscles first; causing dysphagia, dysarthria

- Progresses to involve the phrenic nerve & nerves supplying the accessory muscles of respiration

- Very importantly, there is no sensory deficit

- In ALS, the most common motor neuron disease, the UMN is involved as well

- Peripheral nerve:

- Radiculopathy:

- LMNL due to nerve root disease

- In other words, the deficit conforms to the segmental innervation of the affected motor roots

- Sensory modalities e.g. Pain may be a feature, for example sciatica with weakness

- Polyradiculopathy:

- LMNL due to nerve root disease of multiple nerves, may also be sensory

- Plexopathy (brachial or lumbosacral):

- LMN lesion due to damage of a plexus (brachial or lumbar)

- The deficit that does not conform to mononeuropathies or polyneuropathy

- g. upper arm & shoulder involvement in upper branchial plexus lesions, forearm & hand involvement in lower brachial plexus lesions.

- Mononeuropathy:

- LMN lesion due to single nerve disease

- The deficit conforms to the distribution of a single nerve, e.g. ulnar nerve palsy or radial nerve palsy, median nerve palsy

- Sometimes the nerve is palpable

- Tinel’s phenomenon may occur: tapping the nerve causes a tingling sensation

- Mononeuritis multiplex:

- LMN lesions that begin like a mononeuropathy, but other nerves then become involved

- Therefore it starts asymmetrically i.e. in one arm then progresses to involve other nerves in other limbs

- If seen at the late stage, the disease is diffuse & symmetrical. Therefore the history & progression is important in this case

- Sometimes the nerve is palpable

- Tinel’s phenomenon may occur: tapping the nerve causes a tingling sensation

- Polyneuropathy:

- Develops symmetrically & distally leading to a glove & stocking distribution

- It doesn’t fit into a nerve root (segmental) or multiple peripheral nerve distribution

- Motor, sensory or both

- If sensory: small fibres, large fibres or both

- Small fibres: decreased pinprick & temperature sensation (painful & burning), autonomic dysfunction, but relative sparring of power & reflexes

- Large fibres: areflexia, sensory ataxia

- Radiculopathy:

Patterns for localising motor or sensory deficits:

Lateralised symptoms (e.g. hemiparesis):

- Hemispheric lesions

- Thalamus

- Brain stem

- Less commonly, spinal cord

- Associated with cortical signs (aphasia, apraxia, visual field defect):

- Think of hemispheric lesions

- Associated cranial nerve dysfunction (vertigo, diplopia, dysarthria, ataxia):

- Think of brainstem lesions

Cranial nerve abnormalities:

- Ocular: cranial neuropathy III, IV, VI or midbrain or pons

- Facial: cranial neuropathy VII (motor), V (sensory), or pons

- Bulbar: cranial neuropathy IX, XII, or medulla

One limb or Part of a limb is affected:

- Cortical lesion

- Nerve root (Radiculopathy)

- Mononeuropathy

- Early mononeuritis multiplex

All limbs are affected:

- Cervical spinal cord lesions

- Brainstem lesions (accompanied by cranial nerve findings)

- Peripheral neuropathy:

- Polyneuropathy

- Polyradiculopathy

- Mononeuroritis multiplex

Only lower limbs affected:

- Thoracic spinal cord lesions

- Lumbar spinal cord lesions

- Peripheral neuropathy:

- Polyneuropathy

- Polyradiculopathy

- Mononeuroritis multiplex